Smells like spring

Smells like spring

Got any food?

Owen’s birthday cake

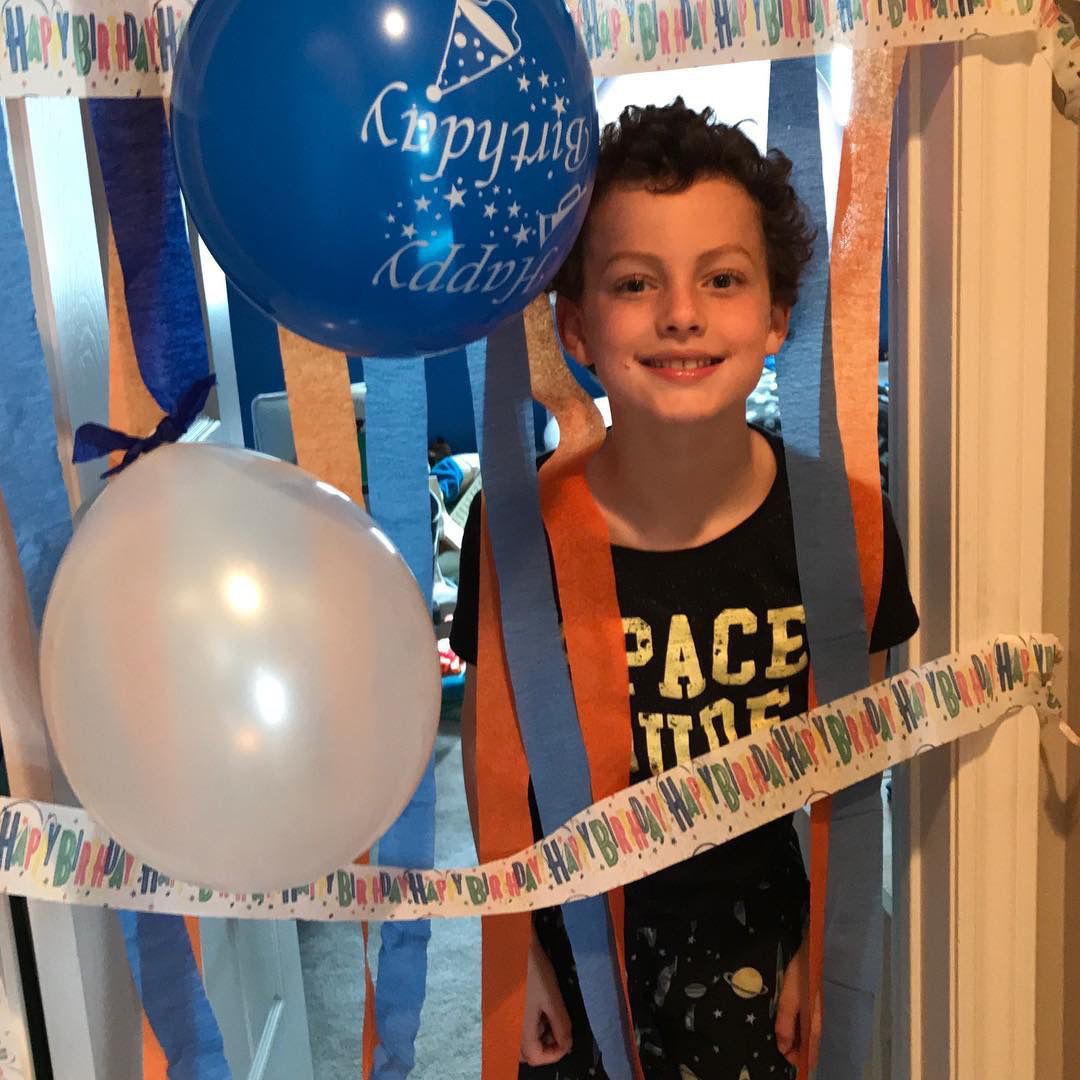

Owen is 9!

Family bike ride

Back at the Old Mill. This time for a conference instead of a wedding.

New bikes

Boy and his dog

Forest walk

Coming out of hibernation