Pollinator networks

Plants are sessile and, consequently, many species rely on pollinators for mating opportunities. However, pollinators do not necessarily visit every individual in a population with equal frequency. Plant attributes, such as floral display and reward provisioning, can influence the frequency of pollinator visitation. Furthermore, aspects of population density and structure may also influence visitation patterns. One effect of this unequal distribution of pollinator activity is that pollinators create networks of connections between plants in which a few plant receive many visits and many plants receive few visits. Such networks are termed ‘scale-free’ and can be contrasted with random networks. Random networks follow a Poisson distribution of connection frequency and have the familiar bell shape characteristic of many biological patterns. Scale-free networks have power-law distributions with no peak, just a steady decline in the frequency of nodes with increasing number of connections. Technically, in a scale-free network the probability that any node is connected to k other nodes is proportional to 1/k^n^, where n is usually around 2.

Measuring networks

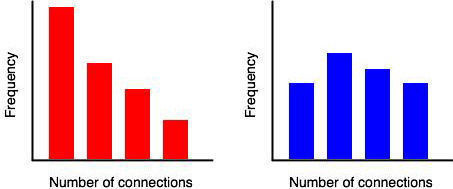

The hallmark of a scale-free network is a hub or node with a high number of connections. A relatively simple test for hubs is to plot a histogram of the number of connections between plants. This is illustrated in the following figures. On the left, many plants have a low frequency of connections, while a few plants have many connections. Those plants with many connections could be hubs. Contrast this with the right. The distribution of connections follows a bell shape with no plants having an excessive number of connections. There are no hub plants in this population.

Importance of scale-free networks

The analysis of scale-free networks has provided insights into fields as diverse as scientific-citation patterns, disease epidemics, world-wide-web structure, and cellular metabolism. Such power suggests that applying network thinking to pollination biology may be useful. These networks are produced through a process of growth and unequal creation of connections. Clearly plant populations experience changes in population size and pollinator behaviour often leads to 'traplining’ or enhanced visitation to particular phenotypes. Consequently, plant populations have some of the prerequisites for scale-free networks. Scale-free networks are very resilient to the random loss of nodes, because the vast majority of network function is provided by the hubs. In a plant population context, if a population can be characterised by a power-law distribution, population growth rates and persistence are likely driven by a small subset of the plants. Such an asymmetry would have important implications for evolutionary ecology and conservation questions.

An important first step is to determine if pollinator-visitation patterns follow a power-law distribution. Hub plants could then be identified and the mechanisms producing the pattern investigated. Are hubs spatially clustered? Do they have larger-than-average floral displays or brighter floral pigments? What are the demographic consequences of removing hubs from a plant population? All we need is data on pollinator visits to plant populations. The data I have access to are inconclusive, mostly because they have insufficient visit frequencies. Any other data sets would be appreciated.

For more information on networks visit www.nd.edu/~networks.