Conscious by Annaka Harris is a fascinating overview of the science of this mysterious process. Her description of panpsychism was particularly intriguing 📚

Conscious by Annaka Harris is a fascinating overview of the science of this mysterious process. Her description of panpsychism was particularly intriguing 📚

The Good Place is a fun, clever show, once you get past the first few episodes 📺

The Bayern Agenda by Dan Moren is a fun sci-fi espionage story. Well worth a read 📚

The Red Rising sci-fi trilogy is solid, page-turning entertainment. Nothing high-concept and sometimes that’s all you want 📚

Visitors Day at Kilcoo

Off to camp for a month!

High school is next!

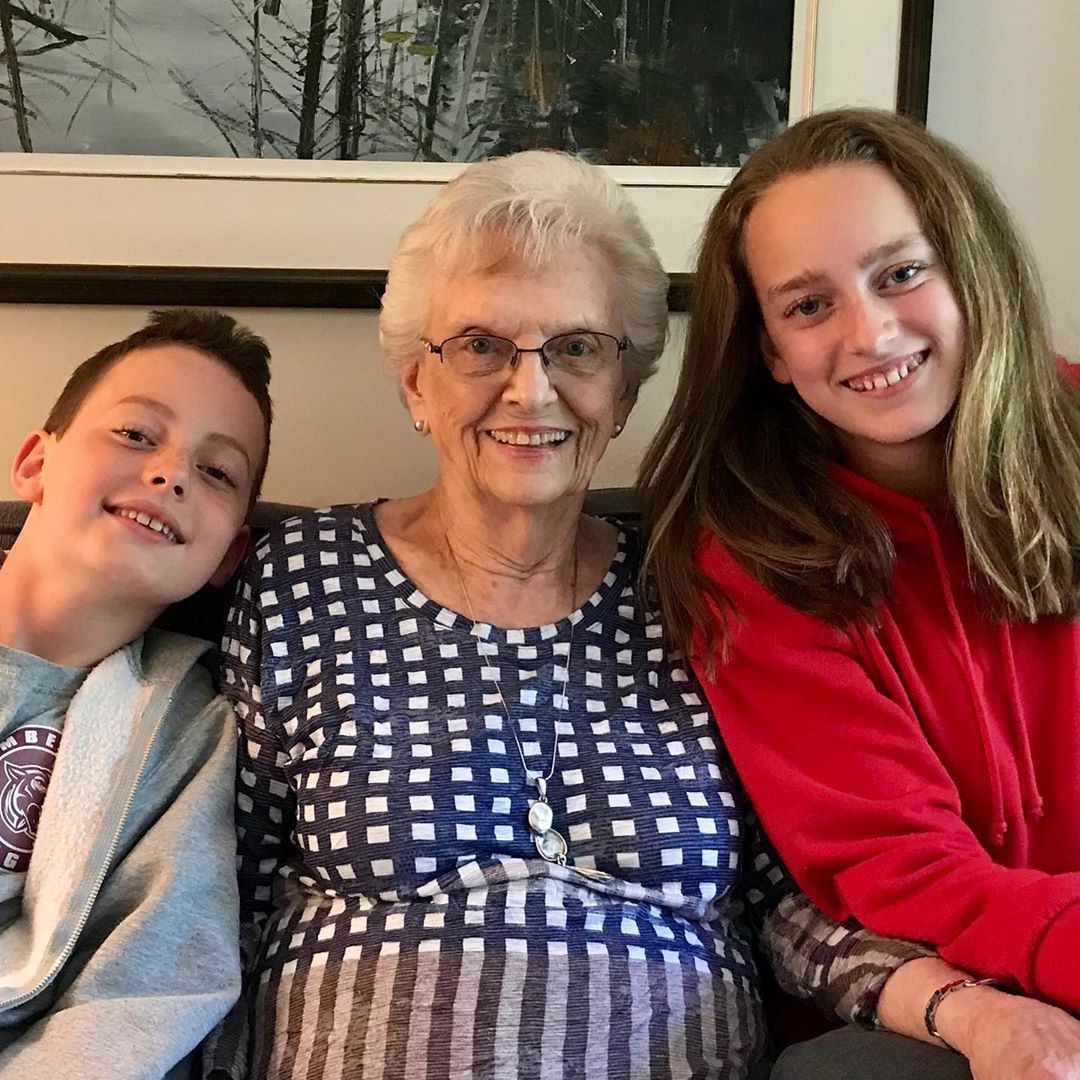

Fun visit with Great Grandma

This CBC story is disheartening:

while nearly two-thirds of Canadians see fighting climate change as a top priority, half of those surveyed would not shell out more than $100 per year in taxes to prevent climate change, the equivalent of less than $9 a month

Better Oblivion Community Center is a good listen 🎵

The Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu was a fun read. The Chinese perspective made it interesting, but the actual appeal was the good science fiction. I’m looking forward to reading the next two books in the trilogy.

Fun mayhem downtown today for the Raptors parade. This was as close as I could get. 🏀🦖

Lucy is ready for @rrrroutley to drop his rib

Great fun at the #spartantoronto race

Switching to summer weather mode ☀️

If you’re at all interested in mindfulness, I recommend checking out the Waking Up app. The guided meditations and lessons are very helpful.

My goal for the home screen is to stay focused on action by making it easy to quickly capture my intentions and to minimize distractions. With previous setups I often found that I’d unlock the phone, be confronted by a screen full of apps with notification badges, and promptly forget what I had intended to do. So, I’ve reduced my home screen to just two apps.

Drafts is on the right and is likely my most frequently used app. As the tag line for the app says, this is where text starts. Rather than searching for a specific app, launching it, and then typing, Drafts always opens up to a blank text field. Then I type whatever is on my mind and send it from Drafts to the appropriate app. So, text messages, emails, todos, meeting notes, and random ideas all start in Drafts. Unfortunately my corporate iPhone blocks iCloud Drive, so I can’t use Drafts to share notes across my devices. Anything that I want to keep gets moved into Apple Notes.

Things is on the left and is currently my favoured todo app. All of my tasks, projects, and areas of focus are in there, tagged by context, and given due dates, if appropriate. If the Things app has a notification badge, then I’ve got work to do today. If you’re keen, The Sweet Setup has a great course on Things.

A few more notes on my setup:

I’ve been using this setup for a few months now and it certainly works for me. Even if this isn’t quite right for you, I’d encourage you to take a few minutes to really think through how you interact with your phone. I see far too many people with the default settings spending too much time scrolling around on their phones looking for the right app.

Like many of us, my online presence had become scattered across many sites: Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Tumblr, and a close-to-defunct personal blog. So much of my content has been locked into proprietary services, each of which seemed like a good idea to start with.

Looking back at it now, I’m not happy with this and wanted to gather everything back into something that I could control. Micro.blog seems like a great home for this, as well described in this post from Manton Reece (micro.blog’s creator). So, I’ve consolidated almost everything here. All that’s left out is Facebook, which I may just leave alone.

By starting with micro.blog, I can selectively send content to other sites, while everything is still available from one source. I think this is a much better approach and I’m happy to be part of the open indie web again.

An entertaining David Gray show, as always

Some great images of maps from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century in First You Make the Maps